New research shows autism may have more in common with strokes than behavior

A board-certified therapist, Casey DePriest has been working with countless autism patients over two decades. Children and adults diagnosed with autism typically get placed on a spectrum of “low-functioning” to “high-functioning”, labels DePriest wishes people would stop using.

She says, “About five years ago I really started looking at new research about motor differences and started to realize this as the missing piece for kids and adults who can’t reliably speak or consistently demonstrate what they know – it’s apraxia. I started to ask, ‘What if instead of seeing autism as a behavioral issue, it was something different with their brain-to-body connection?’”.

DePriest trains people to recognize autism as a motor-sensing problem, not a behavioral disorder. “We compare the movement struggles of autism to those of people who have suffered a stroke, Parkinson’s Disease, or a traumatic brain injury,” she says.

Through this understanding of autism, it’s easier to recognize how autism affects a child’s speech, ability to move, confidence, and academic access – but not necessarily academic achievement. “I’ve found autistic kids were learning language, colors, and so much more all along.”

DePriest’s nonprofit organization, Optimal Rhythms, and their therapeutic day-school called ACCESS Academy, helped shape her understanding of motor differences in autism. “Sometimes kids with autism present to be much younger in their cognition than they are because they are stuck in motor loops on things that are very childish,” says DePriest. She cites an example of adults handing a 15-year-old autistic child an iPad filled with Pre-K aged apps and videos. “It looks like they love it because they keep playing it over and over. This confuses other adults and makes them want to speak to that child in even-simpler terms, or to ‘help’ the child based on a pre-conceived notion.”

In instances like this, DePriest explains the child is stuck in a motor-loop. “If you imagine you’re repeatedly clicking a pen, it gets annoying and people stare at you. You know to stop. Someone with autism can do the same thing, and they notice the stares, but they can’t stop despite wanting to,” she says.

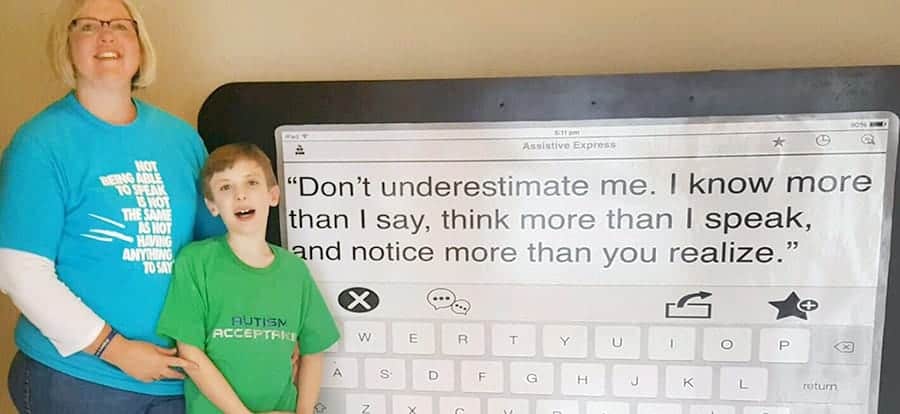

In both instances, the child has normal cognition for a 15-year-old, but their brain can’t tell their body to stop replaying the video or stop clicking the pen. “These kids want to be heard for who they are,” she says. Meaning they are frequently intelligent, kind, and thoughtful children who can’t communicate to adults around them they don’t want to repeatedly watch Dora the Explorer and don’t want “help” from adults to replay it.

DePriest traveled to Indianapolis on November 14 to share her experience, research, and findings with Indiana multidisciplinary team and child first-response professionals. She hopes talks like this will spark more adults to do what she did and help kids address the right kinds of goals. “I needed to forget everything I knew about autism. This was a hard transition because if I was going to shift 180-degrees it meant I had been doing everything wrong for a really long time,” she says.

“But that inspired me to do better,” says DePriest. She’s training people to realize autistic children often have much to say. Indiana child advocacy centers and first responders must be open to new ways of communicating. “A forensic interviewer or police officer who is investigating alleged abuse may ask the child to ‘Sit down in a chair’,” says DePriest. “This seems very simple but can be incredibly challenging. An autistic child has to visualize a path to the chair, move their body, avoid obstacles, stop at the chair, turn around, and sit down,” she notes.

Three motor differences found in autism research

Studies on autism are helping researchers understand three motor differences that can help people understand autism as a motor struggle and not a behavioral problem:

- Difficulty with initiation. “If you see a kid who ‘won’t move’, when asked, like not sitting in a chair, they probably can’t physically move their body. They can’t start,” says DePriest.

- Difficulty with inhibition. “This is not being able to stop our bodies. Like the kid clicking a pen, she wants to stop, but can’t, and it can be more annoying and frustrating for the child than it is for those around the child,” she says.

- Difficulty sustaining or switching a movement. “Like a child asked to walk across a room and sit down, they may struggle with what is a complex motor plan,” she says. “They may start to walk to an intended chair, but overshoot the movement and walk by it and instead sit in another chair.”

In all three cases, failure to start, stop, or correctly move makes many adults believe the child is behaving disrespectfully. “They’re not being a brat. They simply can’t make their bodies move correctly,” says DePriest.

The stakes are high when law enforcement begins an investigation into alleged child abuse. An autistic child may not able to tell adults with speech what’s happened to them. They may struggle to move inside a child advocacy center or be unable to point in a courtroom. “What I encourage interviewers to do is understand what the process might look like to the child. Ask how the child best communicates and what needs they might have or accommodations they might need,” says DePriest. She cites adaptive technology devices and physical stabilization support while moving as two examples.

“In our trainings, we encourage people to think about someone having impaired movement but not necessarily impaired cognition and how to tell the difference. We talk about ways clinicians are trained to communicate with those individuals and about what strategies the clinicians can use to be as impartial and neutral as possible,” she says.

DePriest is adamant in her conversations about autism that, “Just because a child doesn’t speak doesn’t mean they don’t think or have something to say.”

Schools, churches, community groups, and large employers who want to help their members better understand autism can email admin@optimalrhythms.org or call 812-490-9401 to schedule their own training session.